June 18, 2014

The Interstate: More than Roads, More than People

By AASHTO’s Michael Shean

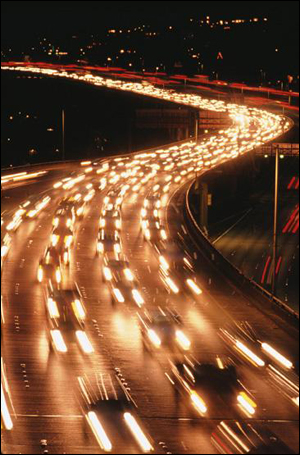

The Interstate system has always held a very strange sort of magic for me.

In the summer of 1988, my parents took my sister and me on the one and only family vacation that we’d ever have. We traveled from my hometown of Beckley, West Virginia, to the cities of Dayton and Cincinnati, Ohio. My father wanted to see the National Museum of the United States Air Force, and the USS Cod. Since as a child I was fascinated with aircraft, I agreed with the trip heartily. My sister was more interested in Sea World, though I could hardly blame her. Dolphins and killer whales, penguins and puffins? Sign me up. It was the longest trip that I had ever taken with my family at that point, and I hardly understood how we would get there —- but I knew at least that we’d be making use of that mythical creature that my parents referred to as “the Interstate.”

I was 10 years old. What did I know about the Interstate?

I knew that it was a system of roads that stretched from one side of the country to the other. I knew that Eisenhower had patterned the whole thing after the German Autobahn and had commissioned it in the 50s (I was a studious child) which at my age felt like the ancient past yet was still recent enough that my grandparents praised it as though it were brand new. I also discovered from my grandfather that the system was built to protect us from the Soviets, with whom the nation still dueled in the waning days of the Cold War. I knew about nuclear war, and I knew that the adults I spent time around were in constant fear of a Soviet invasion. I knew that when the bombs fell — and my grandfather was always certain that they would — we would use it to escape the shadow of Communist oppression.

So what did I know about the Interstate? Before our trip, it had changed in my head from a big system of roads to something terrifying and necessary all at once. By the time we were ready to go, I had visions of Mad Max dancing in my head, our family avoiding the Red Army and hordes of crossbow-wielding, feral humans in leather on motorcycles and braving the blasted landscape in a tiny bronze-colored Renault.

The reality of course, was far less ... exciting ... than I had expected. My initial disappointment soon faded, however, as the miles yielded long roads winding through hills draped with the brilliant green of summer foliage. We crossed over the mighty span of the New River Gorge Bridge, beneath which the river was distant torrent of froth. We passed little towns, the roofs of houses gleaming in the daylight; though I had not yet been on a plane, I thought of how they might have looked like colored flags from on high. Flotillas of tractor-trailers, their cabs painted in a dizzying array of patterns and hues, blew their horns as my sister and I, laughing, waved. Cleveland, with its towers of glittering glass and steel that rose like monuments amongst industrial sprawl, stood venerable and strong along the shimmering face of Lake Erie.

And still the road ran on. Though there were times of boredom — I was 10 years old, after all — these were but islands of tedium in a sea of wonder. I had never appreciated how vast our country was, being a child in his own, small, contained universe, but riding in the back of our family car on that trip the world unfolded before me. The road was ever the real attraction; though we visited the Air Force Museum and Sea World and other places that captured my imagination for the moment, it is the road which I remember, the sights glimpsed from the window of a moving car. When I close my eyes sometimes I can still imagine the wide asphalt ribbon as it was then. Even now, when my wife and I take off on the occasional trip, I feel a vigor that I cannot quite identify or explain when I get behind the wheel. The road calls, and I cannot help but answer.

President Eisenhower may have had the Interstate system constructed to expand the nation’s capacity for travel, commerce, and to provide defense in times of emergency. What it also provided a very young man with a glimpse of the scale of his country, and knowledge of the bewildering array of people that dwell within it. With that, he also provided a spark of wonder that — given the love affair that this nation has had with the automobile since its invention — burns within the heart of many Americans.

I feel that the Interstate system, in this way, has done more than connect us by geography or common roads. The Interstate system was responsible for uniting us ever stronger as a people in the shadow of the Second World War, linking American cities and towns and their populations together in a sense of common nationhood. It is something that I believe persists to this very day, even in the climate of cynicism that suffuses our modern era. In terms of domestic achievements, it is to me Eisenhower’s greatest legacy.

So here I am, at 35. What do I know about the Interstate? I know that nearly 60 years since its completion, the Interstate has never been just a bunch of roads. For our culture, it remains a lifeline.