June 18, 1914

One Hundred Years Ago Today in Transportation...

A major stride in aviation started out on the banks of the River Seine in France when an American named Lawrence Sperry took to the sky in a plane equipped with a new invention of his – the first automatic pilot (autopilot) that was especially made for that mode of transportation. That history-making flight on that sunny Thursday occurred as part of the Councours de la Securité en Aéroplane (Airplane Safety Competition).

The 21-year-old Sperry was a son of Elmer Ambrose Sperry, Sr., a renowned entrepreneur who had helped invent what became an increasingly popular version of the gyrocompass. That large device was designed specifically for use on ships and proved in a couple of key respects to be more reliable than the conventional magnetic compasses as a navigational instrument out at sea. Among other things, the version of the gyrocompass that the elder Sperry helped develop could find true north as determined by the Earth’s rotation and was unaffected by such potentially obtrusive materials as the steel hull of a ship that would distort the magnetic field. By 1914, that gyrocompass had been installed on more than 30 U.S. warships.

Lawrence Sperry, who was highly creative and pioneering in his own right when it came to transportation devices, ended up helping to develop a more lightweight model of that gyrocompass for airborne travel. With characteristic boldness, he decided to publicly introduce that new device – a gyroscopic stabilizer to maintain steadiness and control in the sky -- at that Airplane Safety Competition in France during which various other aircraft improvements would make their debut.

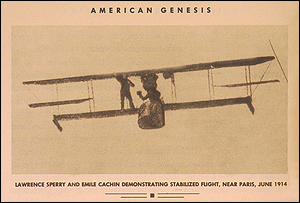

Sperry was assisted in his efforts at that completion by a French mechanic named Emil Cachin. While Sperry spoke little French and Cachin was similarly fluent in English, the two of them still managed to quickly establish a rapport with each other and become sufficiently conversant in their respective languages. The two men mounted the new invention onto Sperry’s single-engine Curtiss C-2 biplane.

There were a total of 57 specially outfitted planes participating in that competition, and Sperry’s own aircraft was listed last on that program. When it was his turn to take flight, Sperry – with Cachin as his passenger – piloted the plane down the river. Sperry soon guided the plane near where the competition’s judges were located, engaged the new device, and flew above with both his hands held high. The earthbound crowd, which included both of Sperry’s parents, began cheering.

On the plane’s second pass, Sperry still kept his hands off the controls while Cachin made his way out onto the starboard wing and about seven feet away from the fuselage. Cachin’s shift onto the wing initially caused the plane to start slanting to one side. The gyroscopic stabilizer, however, quickly took control and rebalanced the plane as it continued soaring along. The crowd cheered even more loudly and a band assembled for the occasion started played a robust rendition of the French national anthem “La Marseillaise.”

For his final pass above the reviewing stand that day, Sperry vacated the pilot’s seat and climbed out onto one wing of the plane while Cachin remained on another wing. Both men stayed in place waving to the crowd below while the plane kept flying along without any problems. A judge named René Quinton exclaimed, “Mais, c’est inoui!” (“But that’s unheard of!”).

Sperry not only won first prize in the competition that day but also forever changed the scope and safety of plane flight. In the time since that milestone, gyroscopic stabilizers and their autopilot descendants have proven critical in keeping planes on course without constant pilot intervention. This, in turn, has helped foster greater air safety by reducing pilot fatigue, enabling those pilots to focus more on other mechanical or navigational issues on board, and facilitating consistent and less erratic flights. Additional information on Sperry’s flight is available here.