November 21, 2013

One Hundred Years Ago Today in Transportation...

Technical World Magazine, February, 1914, pages 914-918

Technical World Magazine, February, 1914, pages 914-918

A major technological breakthrough in transportation took place when wireless messages — sent in Morse code without any direct electrical connections involved — from two railroad stations to a train crew on the move were successfully transmitted. That pioneering test in wireless telegraphy specifically occurred in the northeastern United States between a No. 3 Lackawanna Limited train traveling about 60 miles per hour and the stations located at Scranton, Penn., and Binghamton, N.Y.

Back in 1895, famed Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi came up with a practical method for wireless telegraphy when he was first able to transmit signals over a hill and at a distance of more than one mile. By 1913, that method for sending messages had been further refined to cover even greater distances. It was also readily and successfully used in a variety of applications, a key example being ship-to-shore communications.

It remained to be seen, however, if wireless telegraphy could work as well in the world of railroads. Transmitting such messages to a slow-sailing ship out along an unobstructed area of water was one thing, but similarly communicating with a faster-moving train in regions replete with obstacles both natural and manmade was quite another.

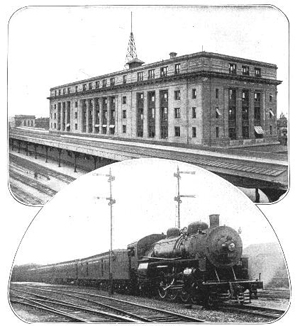

These were the daunting challenges that had to be faced in preparing for those transmission tests along the Lackawanna Railroad line in 1913. That summer, wireless transmitting and receiving infrastructure was built at the Lackawanna Station in Binghamton. That infrastructure encompassed a 97-foot-tall steel tower set up at the east end of that station and a similar one constructed on the west side. A total of four cables spanned between the tops of those towers to form an antenna. In addition, transmitting and receiving equipment was put in place in a small room on the station's second floor.

The same kind of infrastructure was built in the meantime at the Scranton terminal located 65 miles to the south. The Lackawanna Limited train to be used for the experiment was outfitted with a horizontal rectangular aerial 18 inches above each of four cars and linked together by slack wires.

Marconi's idea behind all of these elaborate installations was to have the train be in constant contact with the towers at each station when traveling through those respective areas of coverage – a concept very much like what mobile-phone users experience today when using their devices.

On that Friday evening of Nov. 21, the train began its history-making trek out of Hoboken, N.J., and headed for Scranton. The train maintained contact with the towers at Scranton for 10 minutes after leaving that station for Binghamton. The results at the next set of towers proved even more positive, with the wireless communication between the train crew and those at the Binghamton station staying intact for about 30 miles until reaching Oswego, N.Y.

The results of the test run proved to a cause for celebration despite all potential impediments en route. As the Nevada State Journal newspaper reported the following day, "Messages were sent and received perfectly, although it was through a mountainous country." The train crew for this historic effort were L.B. Foley, telegraph and telephone superintendent; J.J. Graf, telephone engineer; and – in perhaps the most important job of them all – M.L. Berger, described in that same newspaper account as an "expert wireless operator."

Over the next few days, additional tests in wireless communication were conducted with that train and further improvements were made to the process and equipment. A whole new chapter in transportation technology had just been opened.